Research

During early stages of embryogenesis, the developing central nervous system (CNS) appears strikingly conserved across vertebrate species. By the end of gestation, however, the vertebrate CNS has diverged dramatically, giving rise to an extraordinary diversity of species-specific morphologies and functions.

What drives the phylogenetic diversification of the vertebrate CNS?

Neural progenitors are the architects of the CNS, controlling both the types of neurons and glia that are generated, as well as their numbers. The phylogenetically divergent properties of neural progenitors are therefore key drivers of species-dependent variations in the size and cellular composition of the vertebrate CNS.

We aim to elucidate the unique properties of the human neural progenitor population, their underlying genetic factors, and their role in human development and disease.

Projects

Neural progenitor diversity

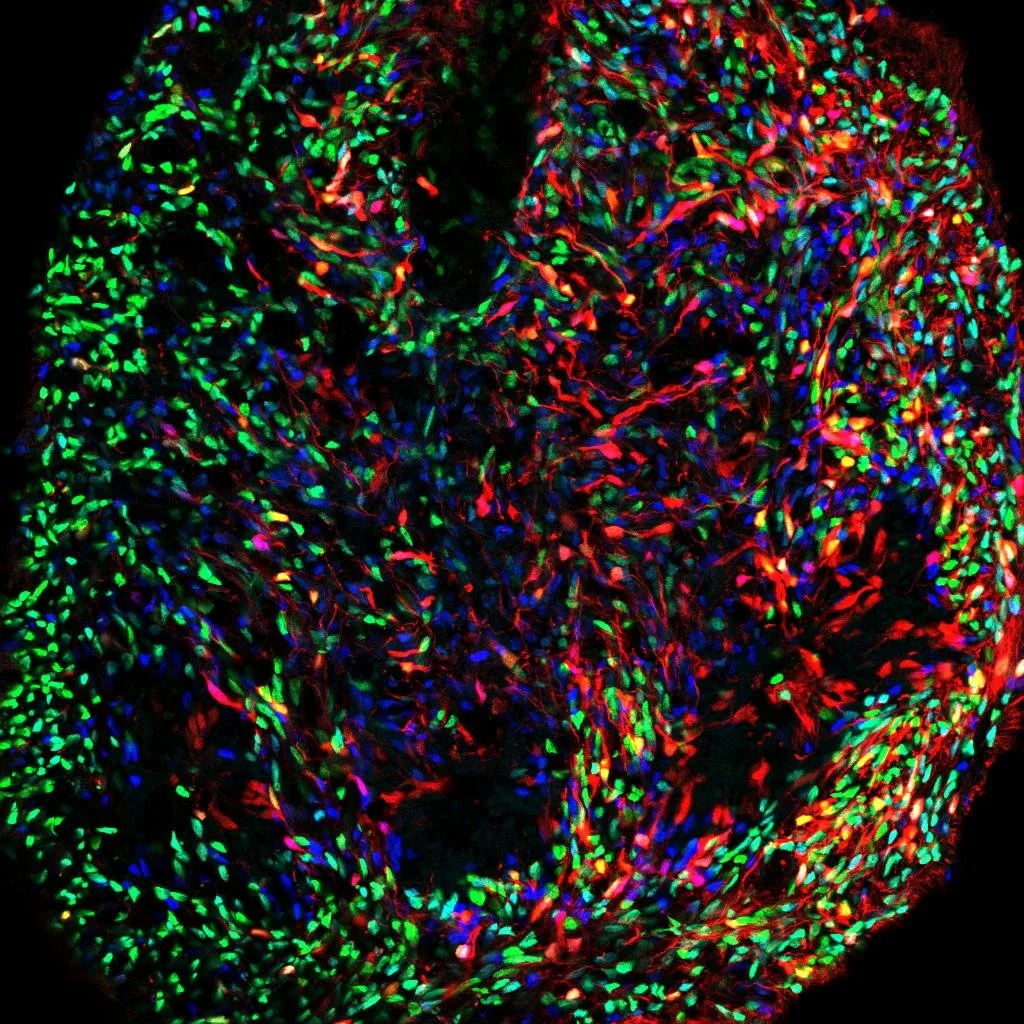

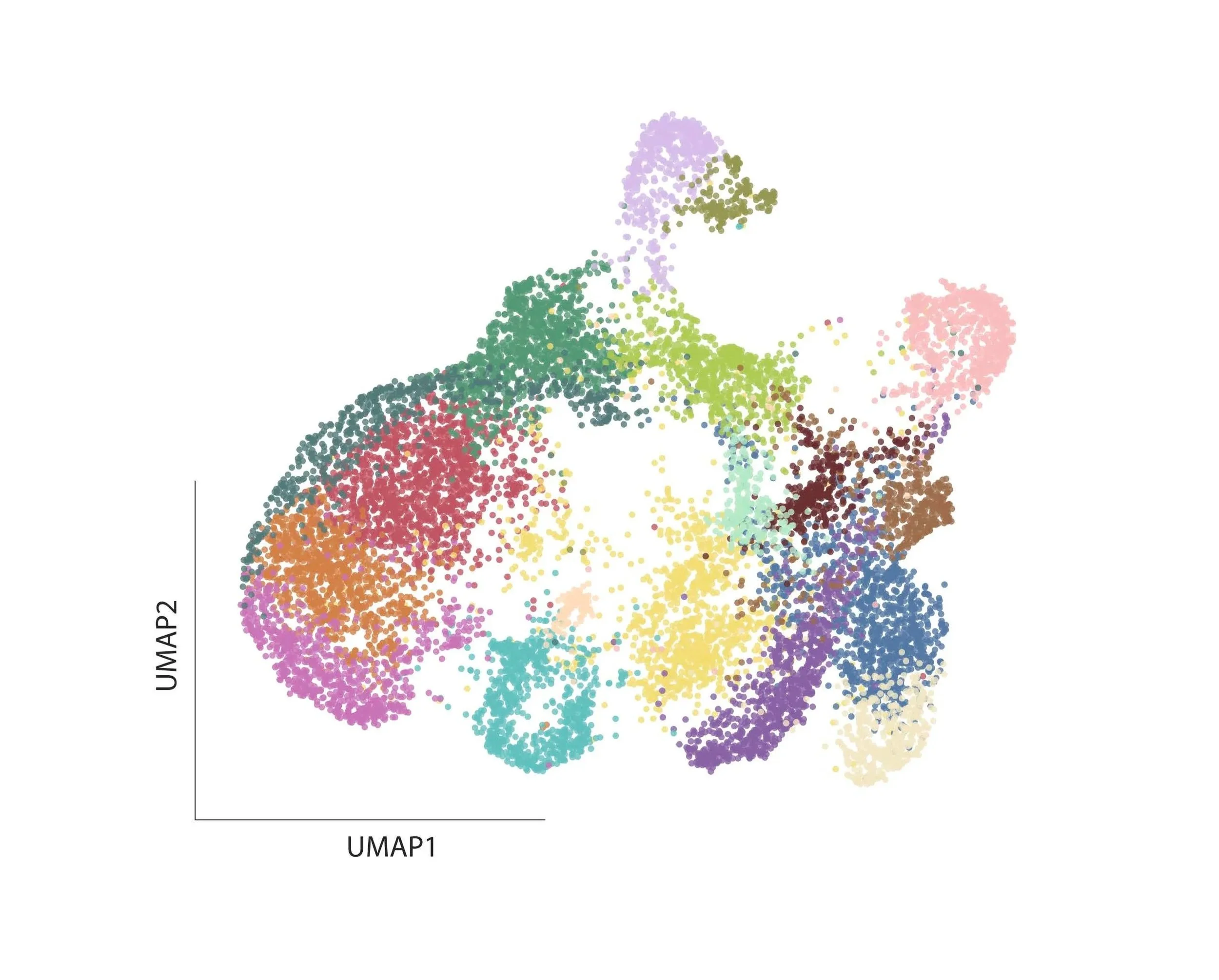

During human development, neural progenitors produce thousands of neuronal cell types, each defined as having distinct molecular, morphological, connectional, and/or electrophysiological properties. In contrast, neural progenitors themselves have traditionally been classified simply by marker gene expression, limiting our resolution as to their evident functional diversity.

To fill this gap in our understanding of neural development, we aim to utilize multiplexed, scalable genetic tools to systematically map the functional diversity of neural progenitors.

Human-specific gene regulation

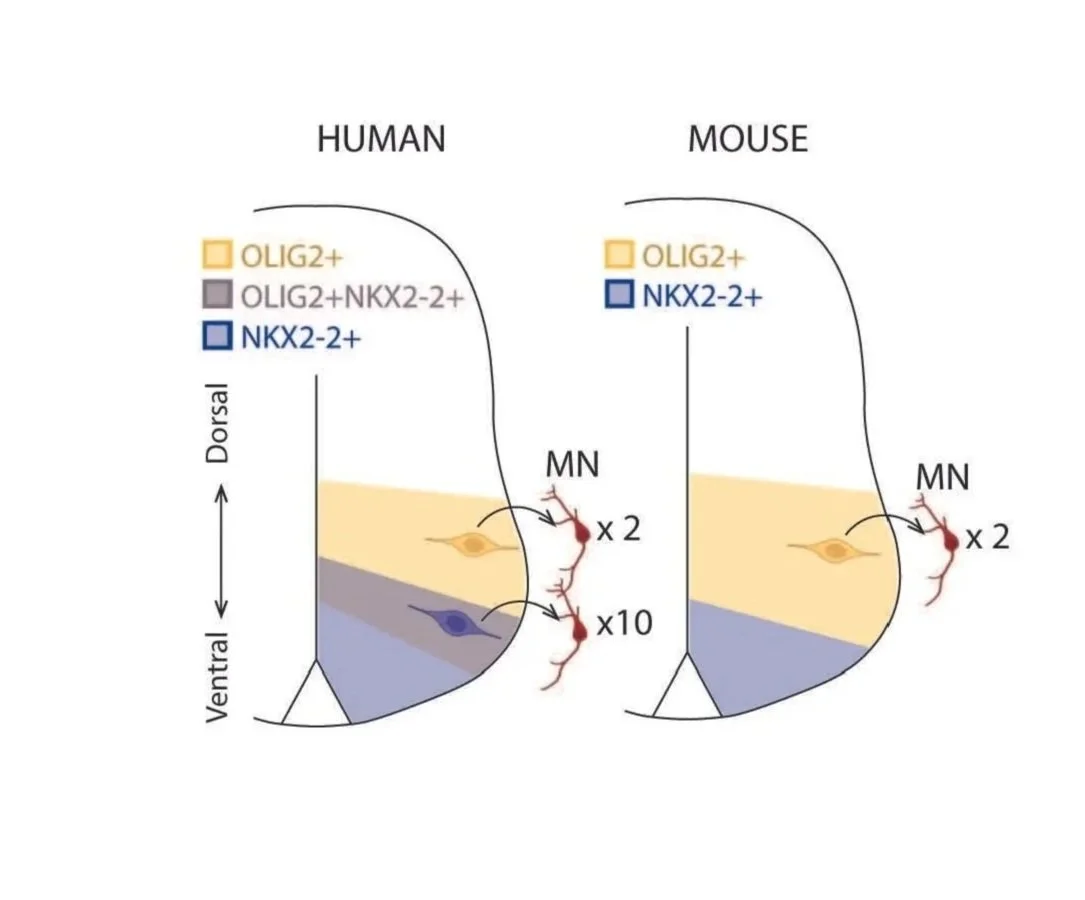

During development, cross-repressive interactions between key transcription factors pattern the neural epithelium into non-overlapping “domains” of neural progenitors. Interestingly, several of the boundaries between these domains are blurred in humans, giving rise to novel, functionally distinct progenitors.

We seek to understand the genetic basis of how these cross-repressive interactions are seemingly weakened in humans, as well as their downstream effects.

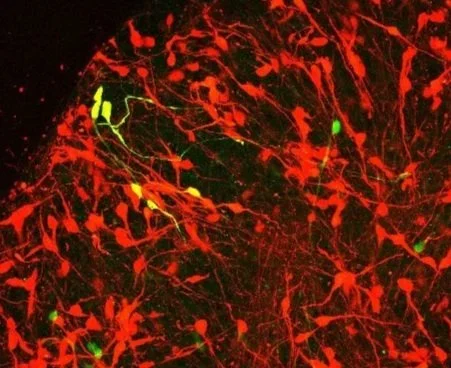

Human diseases

Most cell types in the human CNS are conserved among mammals, yet their susceptibility to disease differs across species. Further, many diseases (like ALS) occur uniquely in humans among closely related primate species. We aim to leverage this phylogenetic variation in disease susceptibility to shed light on key pathogenic pathways.